- Classification

- CHONDRICHTHYES

- LAMNIFORMES

- CETORHINIDAE

-

Fish Classification

-

Class

CHONDRICHTHYES Sharks, rays ... -

Order

LAMNIFORMES Mackeral Sharks -

Family

CETORHINIDAE Basking Sharks -

Genera

Cetorhinus(1)

Family CETORHINIDAE

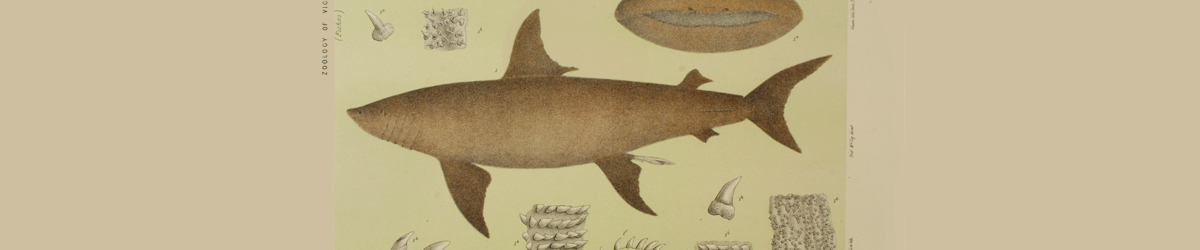

The Basking Shark is the second largest living fish in the world next to the mighty Whale Shark. Despite its huge size and enormous mouth, basking sharks are harmless filter feeders with have thousands of bristle-like gill rakers to strain plankton from the water column. It has a stout streamlined body, 5 huge gill slits that almost encircle the head, a pointed snout with a huge mouth, tiny eyes low on the head, large first dorsal, pectoral and pelvic fins, small second dorsal and anal fin, a lunate caudal fin. Dark greyish-brown above, somewhat paler below.

More Info

|

Family Taxonomy |

The family Cetorhinidae contains a single species, Cetorhinus maximus, the Basking Shark. |

|

Family Distribution |

Worldwide in cool temperate coastal seas and oceanic waters in coastal areas and in the open ocean; occasionally venturing into subtropical waters. Basking sharks are rare in Australian waters, and are known from about Port Stephens (New South Wales) to Busselton (Western Australia) and around Tasmania in depths from the surface to 500 metres. Although this pelagic shark is often seen at the surface, a tagged individual was recorded diving to more than 1200 metres (Gore et al. 2008). Basking sharks may spend much of their time at mesopelagic depths. Basking sharks follow summer plankton blooms and are seasonally abudant in some parts of the world. |

|

Family Description |

Basking sharks have a stout streamlined body, 5 extremely long gill slits that extend from the top to the underside of the head, a pointed snout with a huge mouth that extends well beyond the small eyes that are low on the head; jaws with rows of minute curved teeth; first dorsal, pectoral and pelvic fins large, second dorsal and anal fins small, caudal fin crescent-shaped. |

|

Family Size |

Although basking sharks can grow to more than 12 metres in length and a weight of about 7 tonnes, most individuals are smaller. |

|

Family Colour |

Dark greyish-brown above, somewhat paler below. |

|

Family Feeding |

Basking sharks are filter feeders, and use thousands of bristle-like gill rakers to strain huge quantities of plankton from the water column. In some parts of the world, basking sharks migrate over long distances, gathering to feed in areas of high zooplankton productivity, such as regions where different water bodies mix (thermal fronts). Gore et al. (2008) reported on tagged sharks that undertook a transatlantic migration from the Isle of Man to Newfoundland. Basking sharks are known to feed on copepods, euphasids, fish eggs, chaetognaths and crustacean larvae. |

|

Family Reproduction |

Basking sharks are ovoviviparous probably with intrauterine oophagy. Litters of up to 6 pups are born at about 1.5 metres in length after a long gestation period of more than one year. Male basking sharks mature at 4-5 metres in length, and females at 8-10 metres. |

|

Family Commercial |

Basking sharks were historically hunted for their liver oil, that was used industrially and in street lamps, as well as for its flesh. Now, the large fins are in high demand for sale in the Asian shark fin trade. They are also taken as by-catch in a number of fisheries around the world. |

|

Family Conservation |

IUCN: The Basking Shark has been globally assessed as VULNERABLE on the 2011 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Fowler, 2005). The Northeast Atlantic subpopulation has been assessed as ENDANGERED (Foster, 2009). CITES: Listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). |

|

Author |

Dianne J. Bray |

References

Anderson, R.C. & Simpfendorfer, C.A. 2005. Indian Ocean, pp. 140-149. In: S.L. Fowler, M. Camhi, G.H. Burgess, G.M. Cailliet, S.V. Fordham, R.D. Cavanagh, C.A. Simpfendorfer & J.A. Musick (eds). Sharks, rays and chimaeras: the status of the chondrichthyan fishes. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. FAO species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. FAO, Rome.

Compagno, L.J.V. 1990. Shark exploitation and conservation. In: H.L. Pratt, Jr., S.H. Gruber & T. Taniuchi (eds). Elasmobranchs as living resources: Advances in the biology, ecology, systematics and the status of the fisheries. NOAA Techncal Report. NMFS.

Compagno, L.J.V. 2001. Sharks of the world: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2. Bullhead, Mackerel and Carpet Sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO. Rome, Italy.

Cortés, E. 2008. Comparative life history and demography of pelagic sharks, pp. 309-322. In: M. Camhi, E.K. Pikitch & E.A. Babcock (eds). Sharks of the Open Ocean. Blackwell Publishing.

Dulvy, N.K., Baum, J.K., Clarke, S., Compagno, L.J.V., Cortés, E., Domingo, A., Fordham, S., Fowler, S.L., Francis, M.P., Gibson, C., Martinez, J., Musick, J.A., Soldo, A., Stevens, J.D. & Valenti, S.V. 2008. You can swim but you can’t hide: the global status and conservation of oceanic pelagic sharks and rays. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 18(5): 459-482.

Fowler, S.L. 2005. Cetorhinus maximus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 15 January 2012.

Fowler, S.L. 2009. Cetorhinus maximus (Northeast Atlantic subpopulation). In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 15 January 2012.

Francis, M.P., Duffy, C. 2002. Distribution, seasonal abundance and bycatch of basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) in New Zealand, with observations on their winter habitat. Marine Biology 140: 831-842.

Gilmore, R.G. 1993. Reproductive biology of lamnoid sharks. Environmental Biology of Fishes 38: 95-114.

Gore, M.A., Rowat, D., Hall, J., Gell, F.R. & Ormond, R.F. 2008. Transatlantic migration and deep mid-ocean diving by basking shark. Biol. Lett. 4(4): 395–398.

Harvey-Clark, C. J., Stobo, W. T., Helle, E. & Mattison, M. 1999. Putative mating behaviour in basking sharks off the Nova Scotia coast. Copeia 1999: 780-782.

Hoelzel, A.R., M.S. Shivji, J. Magnussen & M.P. Francis. 2006. Low worldwide genetic diversity in the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). Biology Letters 2: 639-642.

Matthews, L.H. 1950. Reproduction in the basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus). Phil. Trans. B. Royal Soc. Lond. 234: 247-316.

Martin, R.A. & Harvey-Clark, C. 2004. Threatened fishes of the world: Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus 1765) (Cetorhinidae). Env. Biol. Fish. 70: 122.

Natanson, L.J., Wintner, S.P., Johansson, F., Piercy, A., Campbell, P., de Maddalena, A., Gulak, S. J.B., Human, B., Fulgosi, F. C., Ebert, D.A., Hemida, F., Mollen, F.H., Vanni, S., Burgess, G.H., Compagno, L.J.V. & Wedderburn-Maxwell, A. 2008. Ontogenetic vertebral growth patterns in the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 361: 267-278.

Parker, H.W. & Stott F.C. 1965. Age, size and vertebral calcification in the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus). Zoologische Mededelingen (Leiden) 40: 305-319.

Pauly, D. 2002. Growth and mortality of the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus and their implications for management of whale sharks Rhincodon typus. In: Fowler, S.L., Reed, T.M. & Dipper, F.A. (eds). Elasmobranch biodiversity, conservation and management. Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997, pp. 199-208, IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland.

Sims, D.W. & V.A. Quayle. 1998. Selective foraging behavior of basking sharks on zooplankton on a small scale front. Nature 393: 460–464.

Sims, D.W., Southall, E.J., Quayle, V.A. & Fox, A.M. 2000. Annual social behaviour of basking sharks associated with coastal front areas. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267: 1897-1904.

Sims, D.W., Southall, E.J., Richardson, A.J., Reid, P.C. & Metcalfe, J.D. 2003. Seasonal movements and behaviour of basking sharks from archival tagging: no evidence of winter hibernation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 248: 187-196.

Sims, D.W., Southall, E.J., Tarling, G.A. & Metcalfe, J.D. 2005. Habitat-specific normal and reverse diel vertical migration in the plankton-feeding basking shark. J. Anim. Ecol. 74: 755- 761.

Springer, S. & Gilbert, P.W. 1976. The basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus, from Florida and California, with comments on its biology and systematics. Copeia 1976: 47-54.

White, W. 2008. Shark Families Heteroontidae to Pristiophoridae, pp. 32-100. In Gomon. M.F., Bray, D.J. & Kuiter, R.H (eds). Fishes of Australia's Southern Coast. Sydney : Reed New Holland 928 pp.