- Classification

- ACTINOPTERYGII

- PERCIFORMES

- POMACENTRIDAE

- Amphiprion

Genus Amphiprion

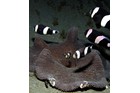

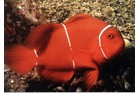

Highly specialized damselfishes that live in association with a number of tropical sea anemones in the Indo-Pacific.

This fascinating partnership was initially thought to be solely for protection: the anemonefishes chase away butterfly fishes that would like to feed on sea anemone tentacles, and in return, the fishes seek refuge among the stinging tentacles of their anemone host.

However, recent studies have shown that anemonefish waste products provide their anemone hosts with essential nutrients. And, although the clownfish nestle deeply among anemone tentacles for rest and protection at night, they remain active by moving around and fanning their fins. This behaviour acts to aerate their anemone hosts at night when oxygen levels are lower because photosynthesis has ceased.

The genus comprises 30 species (Eschmeyer 2012), with 12 known from Australian waters. The genus is broadly distributed in the Indo–Pacific distribution, however, more than one-quarter of the species are either endemic to isolated islands, or have peripheral populations at these remote locations (Fautin & Allen 1997).

The generic name Amphiprion is from the Greek “amphi” (= on two sides, around) and “priön” (= “saw”) in reference to the deeply serrated sub- and pre-opercula bones (part of the gill cover) of Amphiprion species.

Beautiful video of anemonefishes filmed in the Andaman Sea

Video of 11 anemonefish species filmed in Australia, the Solomon Islands, Fiji and Indonesia.

References

Allen, G.R. 1972. Anemonefishes, their classification and biology. New Jersey : T.F.H. Publications 288 pp. 140 figs

Allen, G.R. 1975. Anemonefishes, their classification and biology. Neptune City, New Jersey : T.F.H. Publications 2nd Edn 351 pp.

Allen, G.R. 1991. Damselfishes of the world. Melle, Germany : Mergus Verlag 271 pp.

Bridge T, Scott A, Steinberg D (2012) Abundance and diversity of anemonefishes and their host sea anemones at two mesophotic sites on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs 31: 1057–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00338-012-0916-x.

Cleveland, A., Verde, E. & Lee, R. (2011). Nutritional exchange in a tropical tripartite symbiosis: direct evidence for the transfer of nutrients from anemonefish to host anemone and zooxanthellae. Marine Biology 158: 589-602.

Colleye O., Nakamura M., Frédérich B., Parmentier E. 2012. Further insight into the sound-producing mechanism of clownfishes: what structure is involved in sound radiation? The Journal of Experimental Biology 215: 2192-2202.

Fautin, D.G. 1991. The anemonefish symbiosis: what is known and what is not. Symbiosis 10: 23-46.

Fautin, D.G. & Allen, G.R. 1992. Field Guide to anemonefishes and their host sea anemonies. Perth : Western Australian Museum 160 pp.

- Hobbs J-PA, Frisch AJ, Ford BM, Thums M, Saenz-Agudelo P, Furby KA & Berumen ML. 2013.Taxonomic, Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Bleaching in Anemones Inhabited by Anemonefishes. PLoS ONE 8(8):e70966.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070966

- Holbrook, S.J. & Schmitt, R.J. 2005. Growth, reproduction and survival of a tropical sea anemone (Actiniaria): benefits of hosting anemonefish. Coral Reefs 24: 67-73.

- Litsios G, Salamin N. 2014. Hybridisation and diversification in the adaptive radiation of clownfishes. BMC Evol Biol. 14: 245. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0245-5. Open access

- Litsios, G., Sims, C. A., Wüest, R. O., Pearman, P. B., Zimmermann, N. E., & Salamin, N. (2012). Mutualism with sea anemones triggered the adaptive radiation of clownfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology 12: 212. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-212 Open access

- Mebs, D. 2009. Chemical biology of the mutualistic relationships of sea anemones with fish and crustaceans. Toxicon 54(8): 1071-1074. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.027. Abstract

- Ollerton, J., McCollin, D., Fautin, D. G., & Allen, G. R. (2007). Finding NEMO: nestedness engendered by mutualistic organization in anemonefish and their hosts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274(1609): 591–598. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3758 Open Access

Porat, D. & Chadwick-Furman, N.E. 2004. Effects of anemonefish on giant sea anemones: expansion behavior, growth, and survival. Hydrobiologia 530-531: 513-520.

Richards, W.J. & J.M. Leis. 1984. Labroidei: development and relationships. In H.G. Moser et al. (eds) Ontogeny and systematics of fishes. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Special Publication No. 1: 542-547.

Roopin, M. & Chadwick, N.E. (2009). Benefits to host sea anemones from ammonia contributions of resident anemonefish. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 370: 27-34.

Saenz-Agudelo P, Jones GP, Thorrold SR, Planes S (2011) Detrimental effects of host anemone bleaching on anemonefish populations. Coral Reefs 30: 497–506. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0716-0.

Santini, S. & G. Polacco. 2006. Finding Nemo: Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the unusual life style of anemonefish. Gene 385: 19–27.

Szczebak, J.T., Henry, R.P., Al-Horani, F.A. & Chadwick, N.E. (2013). Anemonefish oxygenate their anemone hosts at night. J. Exp. Biol. 216: 970-976.

Tang, K.L., Stiassny, M.L.J., Mayden, R.L. & DeSalle, R. 2021. Systematics of Damselfishes. Ichthyology & Herpetology 109(1): 258-318.