- Classification

- CHONDRICHTHYES

- LAMNIFORMES

- LAMNIDAE

- Isurus

- oxyrinchus

Shortfin Mako, Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque 1810

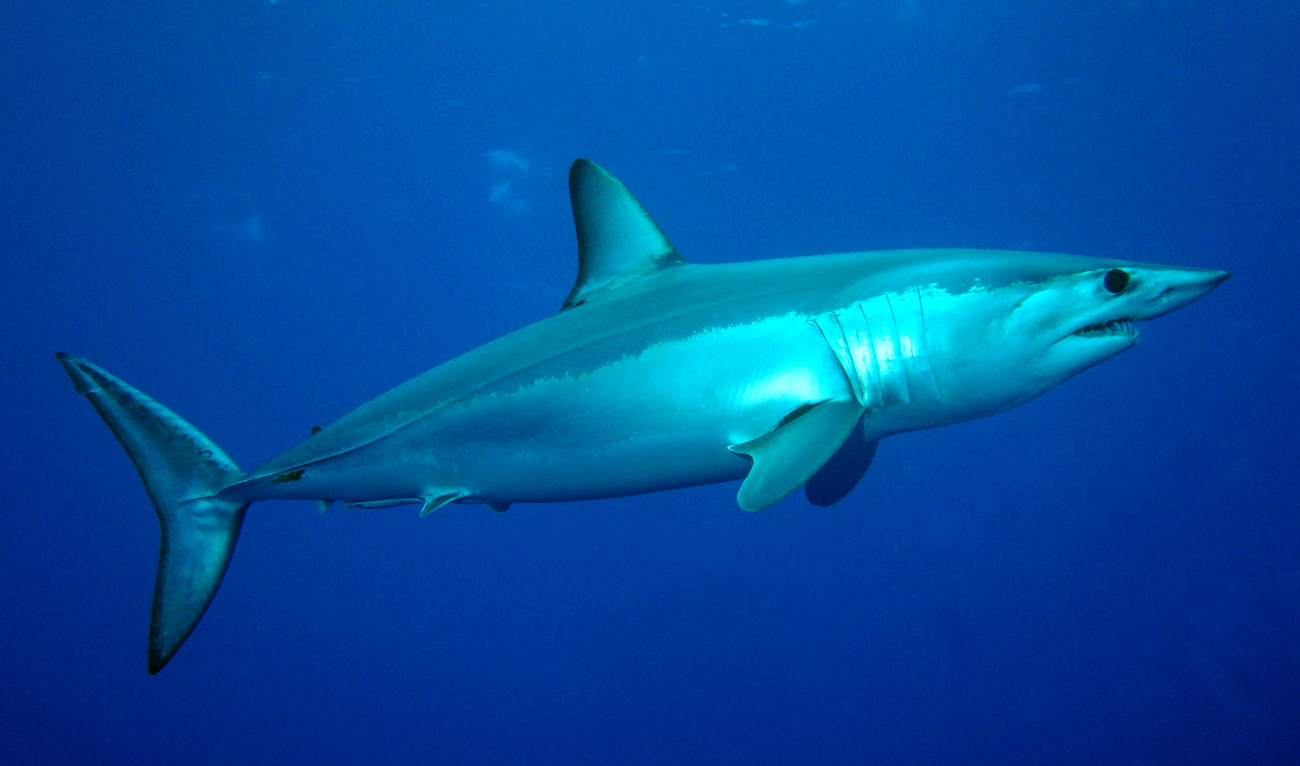

A Shortfin Mako, Isurus Oxyrinchus, off the Azores, North Atlantic, September 2011. Source: Patrick Doll / Wikimedia Commons. License: CC by Attribution-ShareAlike

A very active and powerful pelagic shark with a sharply pointed snout, long slender teeth that protrude from the mouth, very small second dorsal and anal fins and a lunate caudal fin with a single keel on the caudal peduncle. Shortfin Makos are indigo blue above, a lighter blue on the sides and white below.

The Shortfin Mako is considered dangerous and is responsible for unprovoked attacks on humans. The species is known for its extreme speed and is possibly the fastest known shark.

Like other lamnid sharks, it is 'warm-blooded'. It has a heat exchange circulatory system that enables the shark to maintain body temperatures above those of the surrounding water.

Video of a Shortfin Mako by Joe Romeiro

Shortfin Mako, Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque 1810

More Info

|

Distribution |

Recorded in Australia from all states except the Northern Territory - usually in offshore waters. Elsewhere, worldwide in tropical and warm-temperate oceanic waters in depths to at least 500 m, mostly in water temperatures above 16°C. |

|

Feeding |

Known to feed on a wide range of fishes, marine mammals, reptiles and seabirds. Reported prey items include mackerels, tunas, bonitos, swordfish, other sharks, dolphins, marine turtles and seabirds. Shortfin Mako also consume detritus including human trash. |

|

Biology |

Like other sharks in the family Lamnidae. the Shortfin Mako is endothermic or warm-blooded, and has a special heat-exchanging circulatory system that enables it to maintain body temperatures above that of the surrounding seawater. There is a large difference in size at maturity between the sexes. Males mature at 7-9 years, whereas females do not mature until they are 19-21 years of age. The species is aplacental viviparous (ovoviviparous) and oophagous (developing embryos feed on unfertilised eggs with in the uterus). The gestation period is 15-18 months, and there is a three year reproductive cycle. |

|

Fisheries |

Shortfin Makos are targeted in commercial fisheries and taken as bycatch in tuna, shark and billfish longline and driftnet fisheries, particularly on the high-seas. The meat and fins are of high value. The species is also targeted by recreational fishers as a highly-prized gamefish. |

|

Remarks |

Although the Shortfin Mako usually inhabits oceanic waters, it has been implicated in both fatal and nonfatal attacks on humans. The species has also been known to attack boats, and has injured fishers after being hooked. |

|

Author |

Dianne J. Bray |

Shortfin Mako, Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque 1810

References

Anderson, R.C. & Simpfendorfer, C.A. 2005. Indian Ocean. In: S.L. Fowler, M. Camhi, G.H. Burgess, G.M. Cailliet, S.V. Fordham, R.D. Cavanagh, C.A. Simpfendorfer & J.A. Musick (eds), Sharks, rays and chimaeras: the status of the chondrichthyan fishes, pp. 140-149. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

Ardizzone, D., Cailliet, G.M., Natanson, L.J., Andrews, A.H., Kerr, L.A. & Brown T.A. 2006. Application of bomb radiocarbon chronologies to shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) age validation. Environmental Biology of Fishes 77: 355-366.

Bernal, D., Dickson, K.D., Shadwick, R.E. & Graham, J.B. 2001. Analysis of the evolutionary convergence for high performance swimming in lamnid sharks and tunas. Comparative Biochemical Physiology 129: 695-726.

Bishop, S.D.H., Francis, M.P., Duffy, C. & Montgomery, J.C. 2006. Age, growth, maturity, longevity and natural mortality of the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) in New Zealand waters. Marine and Freshwater Research 57: 143-154.

Bustamante, C. & M.B. Bennett. 2013. Insights into the reproductive biology and fisheries of two commercially exploited species, shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) and blue shark (Prionace glauca), in the south-east Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Research 143: 174-183.

Cailliet, G.M., Cavanagh, R.D., Kulka, D.W., Stevens, J.D., Soldo, A., Clo, S., Macias, D., Baum, J., Kohin, S., Duarte, A., Holtzhausen, J.A., Acuña, E., Amorim, A. & Domingo, A. 2009. Isurus oxyrinchus. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 20 November 2012.

Cailliet, G.M., L.K. Martin, J.T. Harvey, D. Kusher & B.A. Welden. 1983. Preliminary studies on the age and growth of blue, Prionace glauca, common thresher, Alopias vulpinus, and shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrhincus, sharks from California waters. NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS 8:179-188.

Campana, S.E., Natanson, L.J. & Myklevoll, S. 2002. Bomb dating and age determination of large pelagic sharks. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 59: 450-455.

Carey, F.G. & Teal, J.M. 1969. Mako and porbeagle: warm bodied sharks. Comparative Biochemical Physiology 28: 199-204.

Carey, F.G., Teal, J.M. & Kanwisher, J.W. 1981. The visceral temperature of mackerel sharks (Lamnidae). Physiological Zoology 54: 334-344.

Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. FAO Species Catalogue. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125. Rome : FAO Vol. 4(1) pp. 1-249.

Compagno, L.J.V. 1998. Families Pseudocarchariidae, Alopiidae, Lamnidae. pp. 1268-1278 in Carpenter, K.E. & Niem, V.H. (eds). The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fisheries Purposes. Rome : FAO Vol. 2 687-1396 pp.

Compagno, L.J.V. 2001. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Rome : FAO, FAO Species Catalogue for Fisheries Purposes No. 1 Vol. 2 269 pp.

Compagno, L.J.V., Dando, M. & Fowler, S. 2005. A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London : Collins 368 pp.

Dulvy, N.K. & J.D. Reynolds. 1997. Evolutionary transitions among egg-laying, live-bearing and maternal inputs in sharks and rays. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B Biol. Sci. 264: 1309-1315.

Francis, M.P. & Duffy, C. 2005. Length at maturity in three pelagic sharks (Lamna nasus, Isurus oxyrinchus, and Prionace glauca) from New Zealand. Fishery Bulletin 103: 489-500.

Francis, M.P. & J.E. Randall. 1993. Further additions to the fish faunas of Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands, Southwest Pacific Ocean. Pacific Science 47(2): 118-135.

Garrick, J.A.F. 1967. Revision of sharks of genus Isurus with description of a new species (Galeoidea, Lamnidae). Proceedings of the United States National Museum 118(3537): 663-690 figs 1-9 pls 1-4

Gilmore, R.G. 1993. Reproductive biology of lamnoid sharks. Environ. Biol. Fish. 38(1/3): 95-114.

Halstead, B.W., P.S. Auerbach & D.R. Campbell. 1990. A colour atlas of dangerous marine animals. Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd, W.S. Cowell Ltd, Ipswich, England. 192 pp.

Heist, E.J., Musick, J.A. & Graves, J.E. 1996. Genetic population structure of the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) inferred from restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of mitochondrial DNA. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 53(3): 583-588.

Hutchins, J.B. & Swainston, R. 1986. Sea Fishes of Southern Australia. Complete field guide for anglers and divers. Perth : Swainston Publishing 180 pp.

Last, P.R., Scott, E.O.G. & Talbot, F.H. 1983. Fishes of Tasmania. Hobart : Tasmanian Fisheries Development Authority 563 pp. figs.

Last, P.R. & Stevens, J.D. 1994. Sharks and Rays of Australia. Canberra : CSIRO Australia 513 pp. 84 pls.

Last, P.R. & Stevens, J.D. 2009. Sharks and Rays of Australia. Collingwood : CSIRO Publishing Australia 2, 550 pp.

Macbeth, W.G., Vandenberg, M. & Graham, K.J. 2008. Identifying Sharks and Rays; a Guide for Commercial Fishers. Sydney : New South Wales Department of Primary Industry 71 pp.

Mollet, H.F., Cliff, G., Pratt, H.L., Jr. & Stevens, J.D. 2000. Reproductive biology of the female shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus Rafinesque 1810, with comments on the embryonic development of lamnoids. Fishery Bulletin 98(2): 299-318.

Oikawa, S. & T. Kanda. 1997. Some features of the gills of a megamouth shark and a shortfin mako, with reference to metabolic activity. Pp. 93-104 in Yano, K., J.F. Morissey, Y. Tabumoto & K. Nakaya. (Eds). 1997. Biology of the Megamouth Shark. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, Japan. 201 pp.

Pepperell, J. 2010. Fishes of the Open Ocean a Natural History & Illustrated Guide. Sydney : University of New South Wales Press Ltd 266 pp.

Rafinesque, C.S. 1810. Caratteri di alcuni Nouvi Generi e Nouve Specie di Animali e Piante della Sicilia con varie Osservazioni sopra i Medesimi. Palermo 105 pp. 20 pls.

Randall, J.E., Allen, G.R. & Steene, R. 1990. Fishes of the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea. Bathurst : Crawford House Press 507 pp. figs.

Randall, J.E., Allen, G.R. & Steene, R. 1997. Fishes of the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea. Bathurst : Crawford House Press 557 pp. figs.

Russell, B.C. & W. Houston. 1989. Offshore fishes of the Arafura Sea. The Beagle 6(1): 69-84.

Schrey, A. & Heist, E. 2003. Microsatellite analysis of population structure in the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 60: 670-675.

Sepulveda, C.A., Kohin, S., Chan, C., Vetter, R. & Graham, J.B. 2004. Movement patterns, depth preferences, and stomach temperatures of free-swimming juvenile mako sharks, Isurus oxyrinchus, in the Southern California Bight. Marine Biology 145(1): 191-199.

Stead, D.G. 1963. Sharks and Rays of Australian Seas. Sydney : Angus & Robertson 211 pp. 63 figs.

Stevens, J.D. 1983. Observations on reproduction in the shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus. Copeia 1983(1): 126-130.

Stevens, J.D. 1984. Biological observations on sharks caught by sports fishermen off New South Wales. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 35: 573-590.

Stevens, J.D. 1994. Family Lamnidae. pp. 141-143 figs 112-114 in Gomon, M.F., Glover, C.J.M. & Kuiter, R.H. (eds). The Fishes of Australia's South Coast. Adelaide : State Printer 992 pp. 810 figs.

White, W. 2008. Shark Families Heterodontidae to Pristiophoridae. pp. 32-100 in Gomon. M.F., Bray, D.J. & Kuiter, R.H (eds). Fishes of Australia's Southern Coast. Sydney : Reed New Holland 928 pp.

White, W.T., Last, P.R., Stevens, J.D., Yearsley, G.K., Fahmi & Dharmadi. 2006. Economically Important Sharks and Rays of Indonesia. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia.

Whitley, G.P. 1940. The Fishes of Australia. Part 1. The sharks, rays, devil-fish, and other primitive fishes of Australia and New Zealand. Sydney : Roy. Zool. Soc. N.S.W. 280 pp. 303 figs.